We went to an outdoor, fire lit performance of Noh theatre at the Kamakura-gu shrine last night.

I had not expected to find Noh very easy. Of the two major forms of Japanese theatre, Noh and Kabuki, Noh is by reputation the hardest to approach. Kabuki has all the exuberant populism of Shakespearean theatre. It traces its roots back to dance and light drama performances in Kyoto in 1603, about the same time Shakespeare was writing Othello, and has always retained its popular feel. It was a particular obsession of old Tokyo (known as Edo). Edward Seidensticker's history of Tokyo quotes an old aphorism that "the son of Kyoto ruined himself over dress, the son of Osaka ruined himself over food and the son of Edo ruined himself looking at things ... Performances were central to Edo culture, and at the top of the hierarchy, the focus of Edo connoisseurship, was the Kabuki theatre... The great Kabuki actors set tastes and were popular heroes and the Kabuki was for anyone, except perhaps the self-consciously aristocratic, who had enough money. " (Just as a footnote on the Shakespeare comparison, one of the main plays at the Kabuki-za this summer was a Kabuki reinterpretation of Twelfth Night, which the director says he intends to take to London soon. It was a hit over here.)

Anyway, I've always fought slightly shy of Noh because it has none of this populism. It has a much longer history than Kabuki and is essentially a religious ceremony, performed on consecrated ground and always telling stories connected with death. Its dramas are very simple, stretched out over long periods with extended poetic monologues and very slow stage movements. The main character wears a mask. You cannot even see a face. Modern Japanese people have difficulty understanding the archaic language so you would have thought it would be a complete nightmare for a dope who can't even understand all the train station announcements.

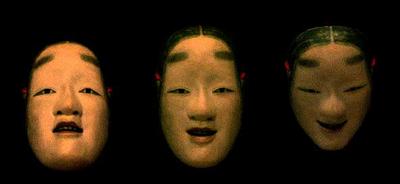

But no! I suppose the fact that Noh's words are fairly incomprehensible and that they are really designed to provide a beautiful context for the movement on the stage actually makes the drama rather easy to appreciate for the non-Japanese speaker. There is word-play in Noh, but these are not fast, wise cracking stories that can turn on a few dramatic words. As long as you mug up on the often very simple tale before the performance, you can actually understand quite a lot of the context of the actors' lyrical movements and focus your mind on the wonder of the Noh mask: although its expression is completely fixed, the performer seems to fill the seemingly blank face with changing feeling by skillfully moving it in the light.

With the firelight playing on the masks, against the dim backdrop of a forested hillside just starting to turn into autumn reds and yellows, it was certainly the most compelling outdoor drama I have ever attended. The first story we watched was a beautiful story called Izutsu. There was then a comic interlude and then a play called Zegai, about two demons fighting Buddha. We were not allowed to take photos during the performance but below is a pic of the setting taken beforehand and one borrowed from the programme of the start of the drama .

1 comment:

Bakire kızla kendi evinde annesi gelmeden kızlık bozuluyor ve anal porno yapmaya devam ediyor azgın genç çiftlerimiz.

Post a Comment